7th April 1788 – 27th December 1845

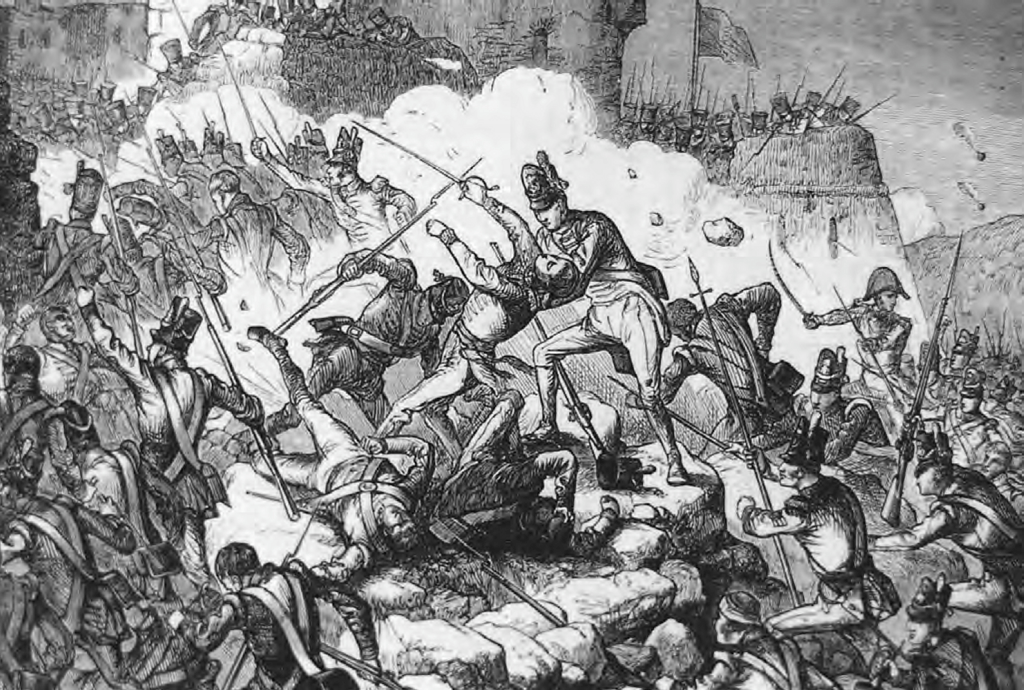

Colonel John Gurwood was an officer in the British army who fought in the Peninsular War (1808 – 1814) against Napoleon’s army. He took part in 15 battles, including the Siege of Ciudad Rodrigo in 1812. During the siege he successfully led a forlorn hope attack. A forlorn hope was the name given to the group of soldiers who were at the forefront of an operation, usually against a defended position, and as such bore the brunt of the enemy’s firepower. The name derives from the Dutch veloren hoop, meaning lost heap. Chances of survival in a forlorn hope were slim. Despite this, there was an eagerness to take part amongst many soldiers thanks to the rewards on offer should they survive, usually in the form of money and promotion, as well as the glory and respect that came with having been part of a forlorn hope. Junior officers in particular were keen to lead a forlorn hope as survival would almost guarantee promotion and an enhancement to his military career prospects.

During the attack John was able to capture the French Governor of Ciudad Rodrigo and escort him to the Duke of Wellington. Wellington then presented John with the Governor’s sword. Despite surviving the attack , John Gurwood sustained a severe head injury which would cause fainting fits, depression, and insomnia at various points for the rest of his life. In 1815, John fought in the Battle of Waterloo. His horse was killed from under him and John was wounded in the knee.

After the war John became concerned about the suffering of the ordinary soldiers now back in England. Periods of drought and wet summers had impacted grain production, raising the price of bread. Disease was rife, especially typhus, and the country was heavily in debt due to the recent war. John, like many other officers, helped soldiers by giving them money and trying to find them employment. He also made a case for them to receive pensions. He asked the Duke of Wellington to bring the matter to the attention of Lord Palmerston, the Secretary at War. The disappointing response was that the pension fund was already over-subscribed, with the Duke admitting to John that the interests of common soldiers had suffered from a lavish liberality extended towards officers.

In 1823 John was in Paris where he met a woman called Finette Mayer. Finette was married and had a daughter, Eugenie, although she was estranged from her husband. John and Finette formed a relationship and in 1826 they had a daughter, Adele. By 1834 Finette and John married, so her husband must have died in the meantime. They had a second daughter, Zumala, named after a Basque general, in 1835.

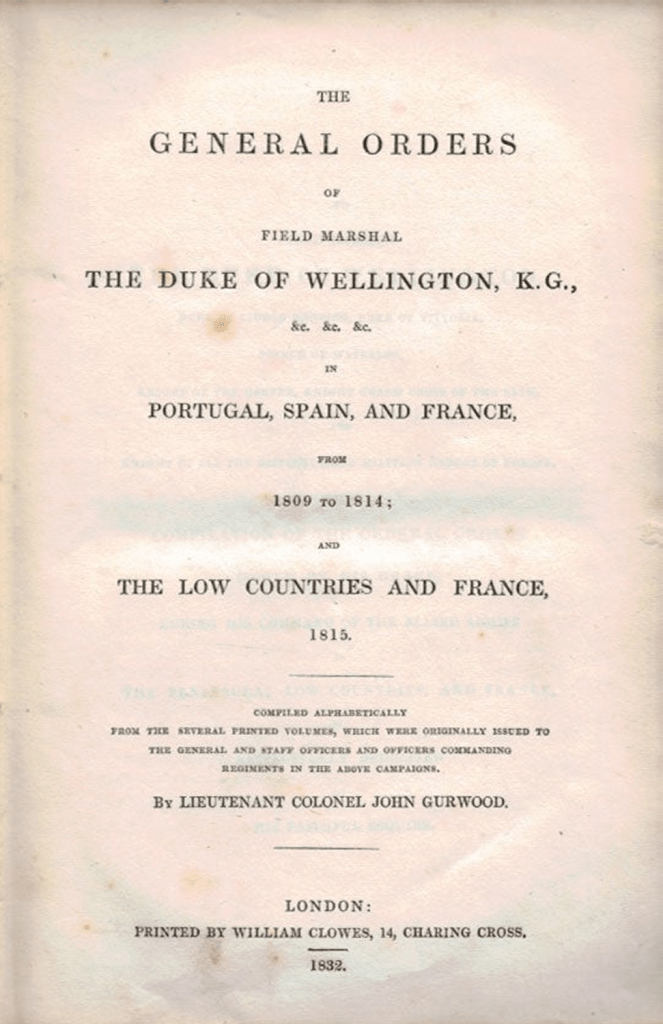

The Duke of Wellington issued detailed Orders and Regulations on a daily basis to the army. They covered everything from the men’s rations to the care of the horses, maintenance of the equipment to distances to be marched. In all they amounted to seven volumes; John edited them down to one volume. The Duke gave John permission to publish the book in 1832. It proved to be popular and soon sold out. Wellington’s friend, Charles Arbuthnot, said that the Duke was so delighted with reading his old orders that he did nothing else all day but read them aloud.

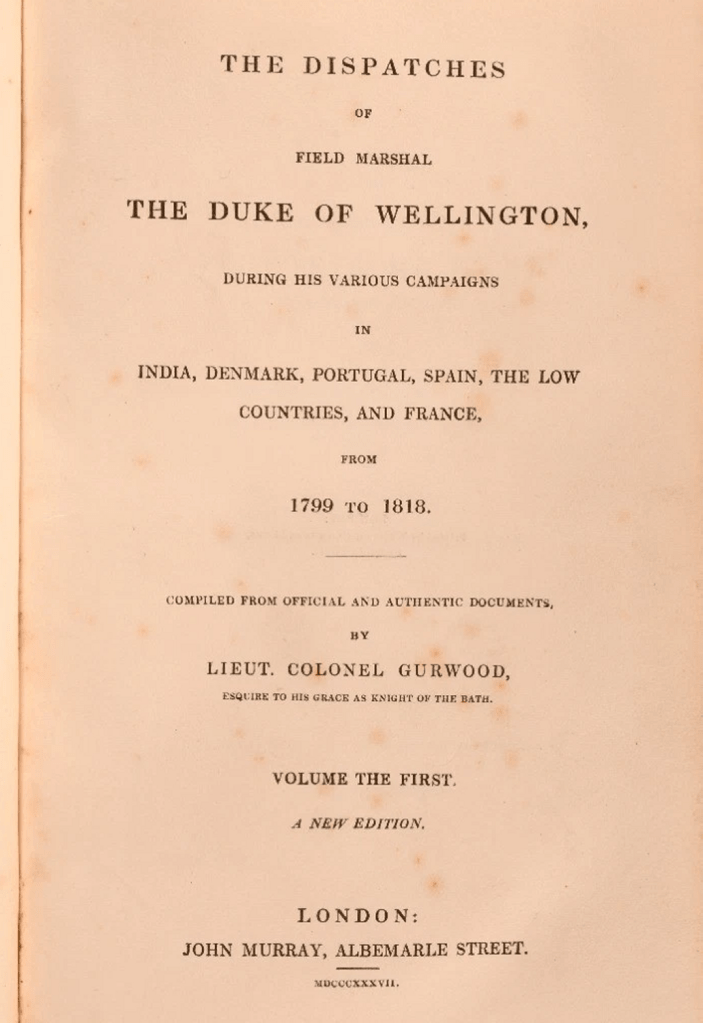

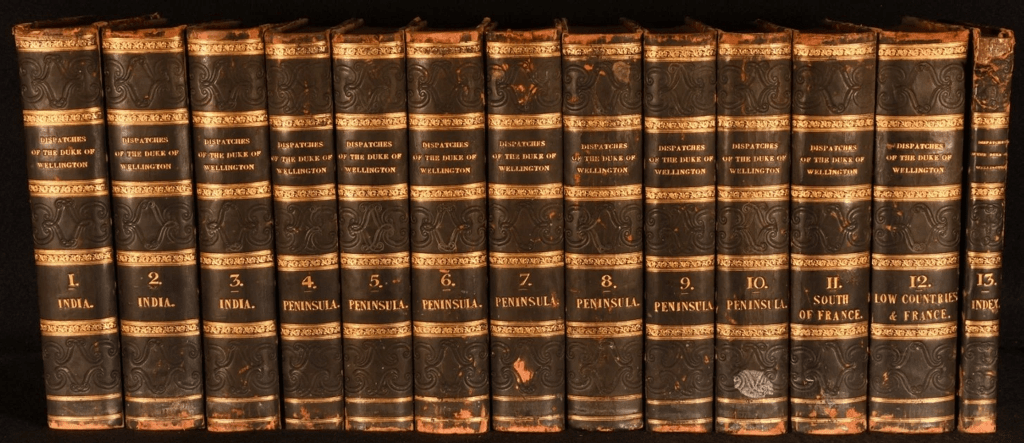

John Gurwood then had the idea of publishing the Duke’s dispatches, from his time in India in the late 1790s up to Waterloo in 1815. He proposed the idea to Wellington in January 1833; the Duke agreed and endeavoured to help him by locating all of his relevant papers, which at times resulted in day after day of searching in his home. Wellington was involved in every step of the publishing process, reading all the documents, and approving printer’s sheets and final proofs.

Volume One was published in 1834, with volumes Two and Three following the next year. The final volume Twelve came out in 1838. The speed with which the Dispatches were published indicates how well John and the Duke worked together. The Dispatches were very popular and several reprints were required to satisfy public demand. A second edition of Dispatches followed in the 1840s.

In 1838 John was made a Companion of the Bath and the following year the Queen of Portugal made him a Knight Commander of the Tower and the Sword. In 1839 he was appointed Deputy Lieutenant at the Tower of London on the recommendation of the Duke, who was the Constable of the Tower.

John suffered from ill health, with occasional fainting fits, which his friends put down to the level of work he was undertaking with the Dispatches. His half-brother believed his head wound from 1812 was partly to blame, as did some physicians. In late November and into December of 1845 he suffered from severe insomnia, going several days at a time without sleep. On the 28th November he wrote to a friend that the last volume and Index have upset me and I have been confined to my room with insomnia for ten days – not a wink of sleep! On the 15th December he said that the insomnia continued undiminished and was accompanied by a fever.

On the 27th December, whilst his wife and two daughters were out for a walk, John Gurwood cut his own throat. An inquest recorded a verdict of temporary insanity, thus allowing his body to be buried in consecrated ground. The Duke of Wellington gave permission for John’s body to be interred in the vaults of the Tower of London.

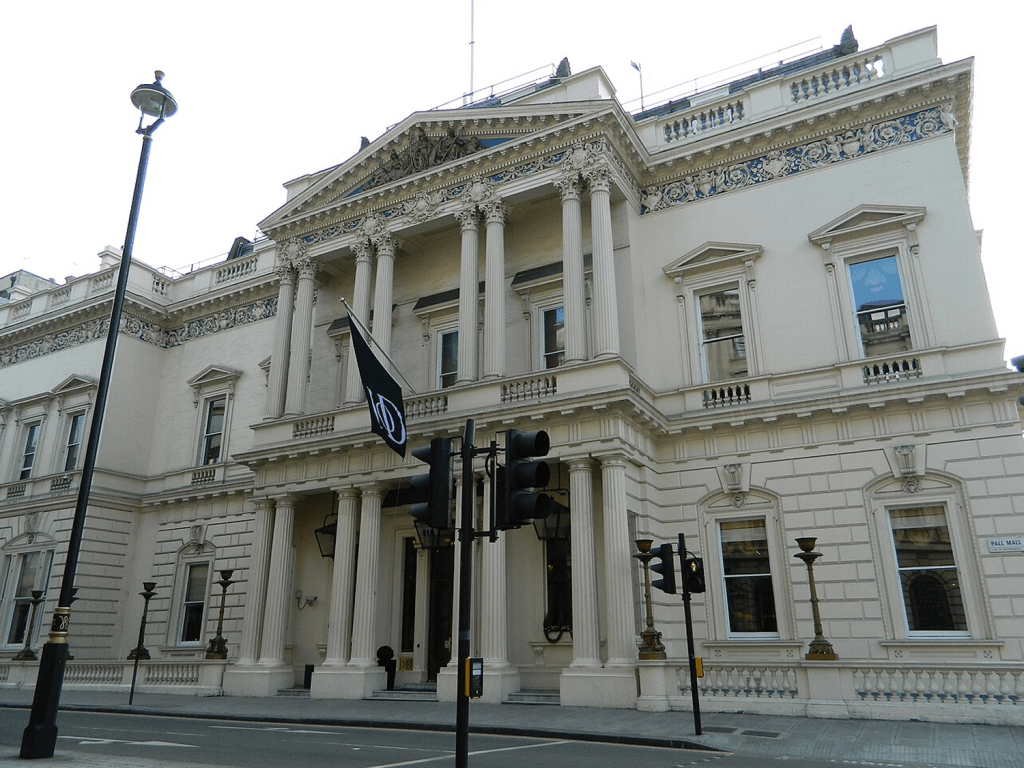

And so to John’s letter. It was written at the United Service Club. This was an officers’ club in London that was founded in 1815 and continued all the way through to 1978.

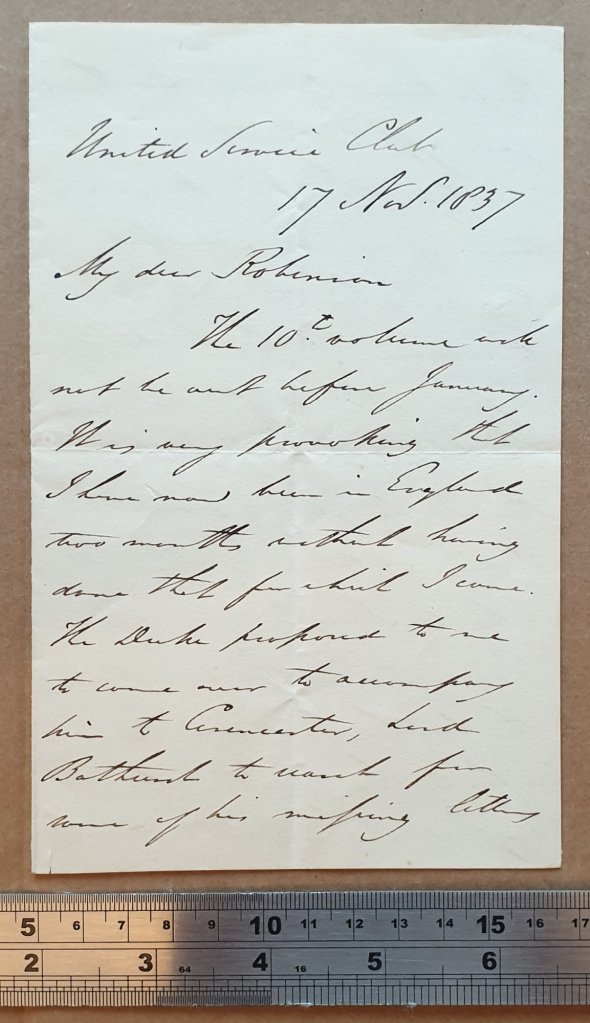

United Service Club

17 Nov. 1837

My dear Robinson

The 10ᵗʰ volume will

not be out before January.

This may ------- that

I have now been in England

two months without having

done that for which I came.

The Duke proposed to me

to come over to accompany

him to --------, and

Bathurst to wait for

some of his ----- letters

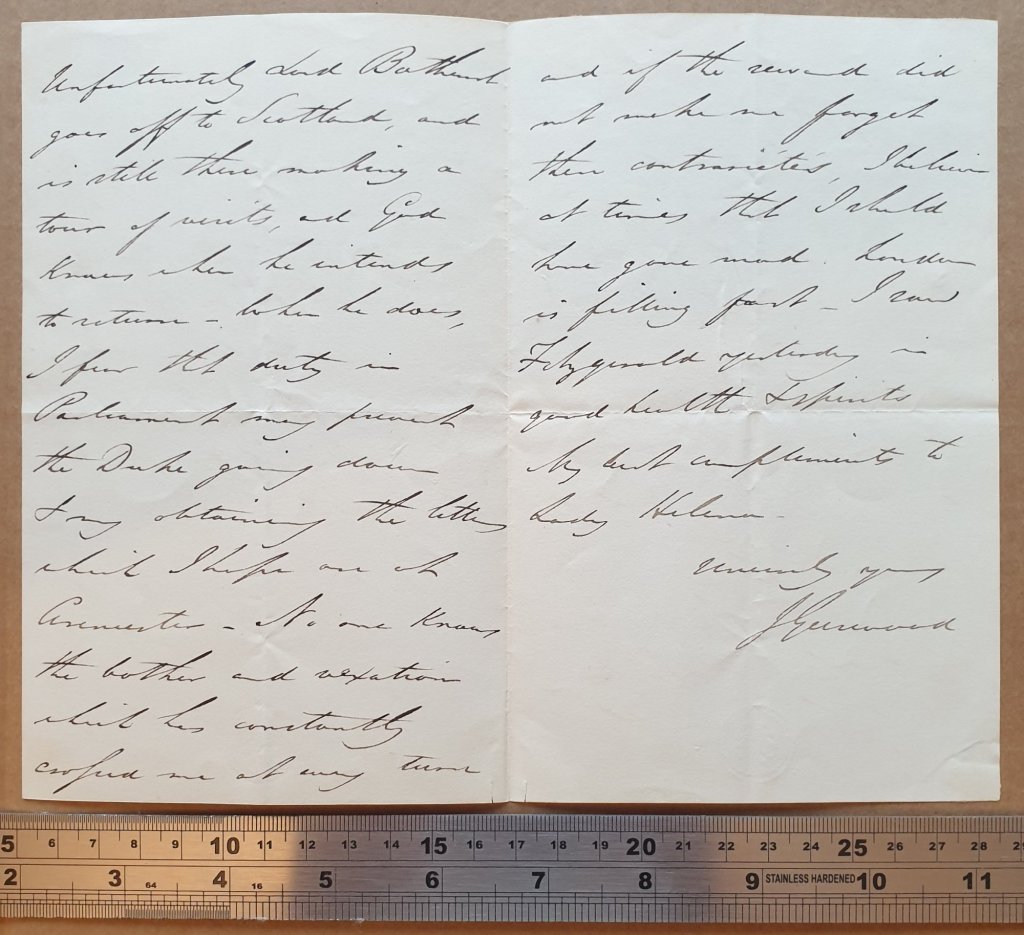

unfortunately and Bathurst

goes off to Scotland, and

is still there making a

tour of units, and God

knows when he intends

to return. When he does,

I fear that duty in

Parliament may prevent

the Duke going down

& my obtaining the letters

which I hope are of

------. No one knows

the bother and vexation

which his constantly

----- me of my time

and if the ----- did

not make me forget

these contrarities I believe

at times that I should

have gone mad. London

is filling fast. I saw

Fitzgerald yesterday in

good health & spirits.

My best compliments to

Lady Helena.

Sincerely yours

J Gurwood

The ending offers a clue as to the identity of the recipient. As the letter is addressed to a Robinson, and it is reasonable to assume that Lady Helena is his wife, then she must be Lady Helena Robinson. Such a Lady was alive at the time and her husband was Sir Richard Robinson, 2nd Baronet Robinson, of Rokeby Hall. The Robinsons spent a lot of time living in Paris, where John met his wife, so it is possible they met there. As aristocrats they would move in the same circles as the Duke of Wellington and so that could be another way in which John knew of them.

John makes reference to the upcoming 10th Volume, so this was clearly written in the midst of his work on the Dispatches. What also comes through is the stress that he is under. I am pleased that the Duke is mentioned.

19th December 2025

Leave a comment