This is the first of what I envisage will be more than one post about a very special letter. When I first became aware of its availability in early December 2025, I took a couple of days to ponder upon the purchasing of it. At over three times the price of my then-current dearest letter, I had to be sure that I wanted it. I decided I did.

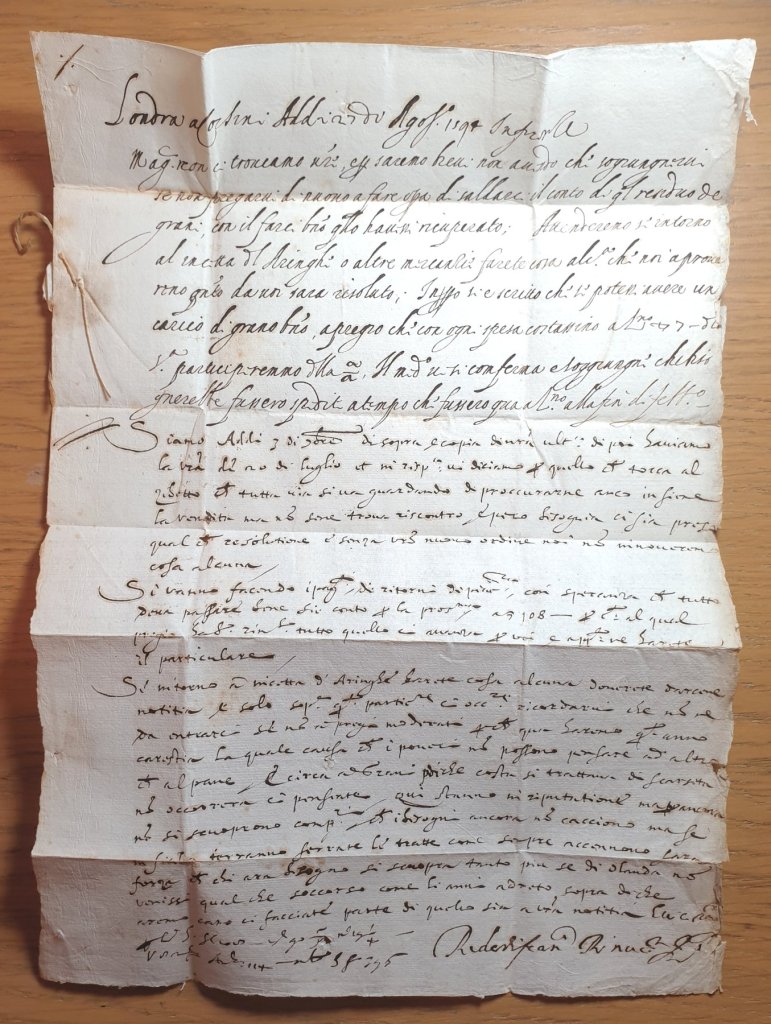

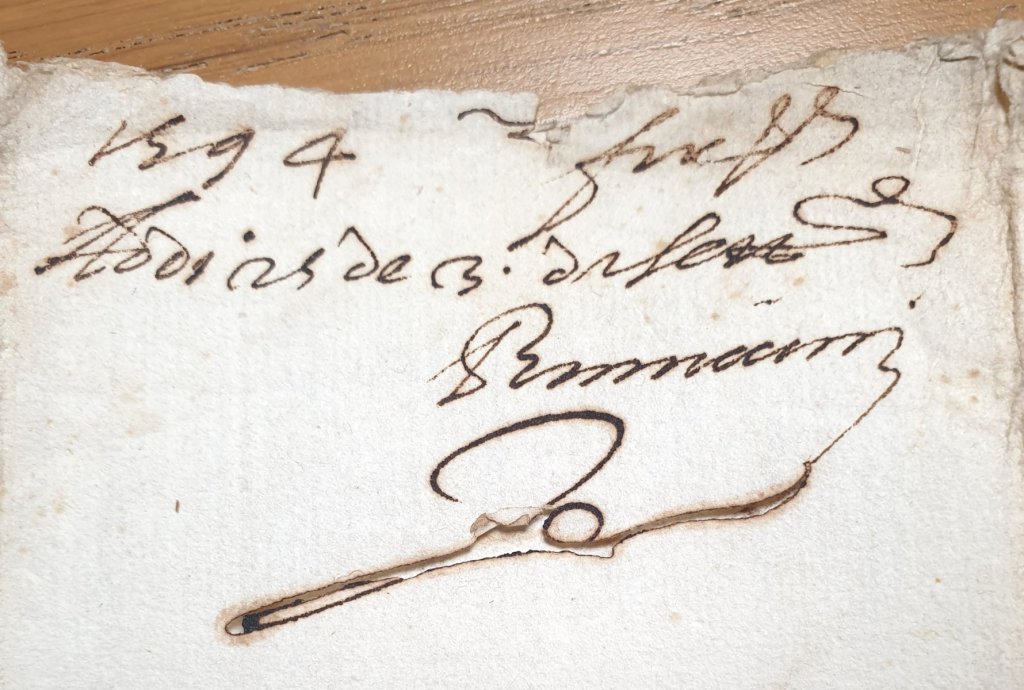

At the time of going to pixel I do not yet know the authors, except to say there are two of them, and I hadn’t heard of the recipient before purchasing the letter. I do not even yet know what the letter says. What makes the letter special is its age. It was written on the 27th August 1594, making it, as of January 2026, a little over 431 years old.

The Corsini Brothers

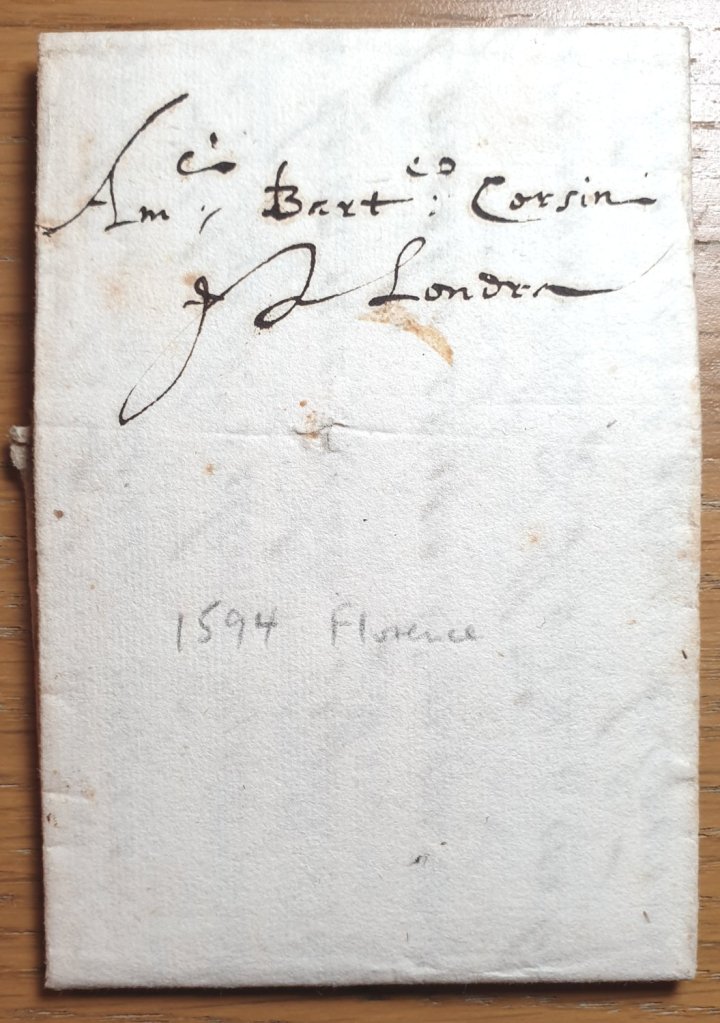

The letter is addressed to Bartolomeo Corsini. The Corsinis arrived in Florence, Italy, at the end of the 12th century. In the 1300s the family fortune began to grow with the Corsinis coming to prominence in this century as politicians, traders, and members of the clergy.

The family’s wealth grew to vast proportions in the late 1500s thanks to Filippo and his younger brother Bartolomeo, the recipient of our letter. Filippo moved to London in 1559 and within 10 years he was the largest importer of European goods to England and a significant exporter of English goods to the Continent. In 1567 the brothers began a trade between Italy and England. Grains and fabrics, originally from the East and processed in Florentine workshops, were sent to England whilst herrings made their way in the opposite direction to Italy. Bartolomeo joined Filippo in London in 1569. The brothers established a commercial office in Gracious Street (now Gracechurch Street) and started a banking and brokerage business with activities around Europe. The Corsini brothers used their immense wealth to purchase a large number of properties in Italy and Bartolomeo took legal steps to ensure that they stayed within the Corsini family for many future generations.

The Age in Perspective

It is important to paint a picture of the era from which this letter originates. Written in Florence, Italy, on the 27th August 1594, Bartolomeo would most likely have received it in London around October 1594. Queen Elizabeth, daughter of Anne Boleyn and Henry VIII, was in the 36th year of her reign. She would continue to be monarch until her death nine years later in 1603. The Spanish Armada had been defeated just six years previously in 1588 and Sir Francis Drake was still at sea. Oliver Cromwell and Charles I, the protagonists of the English Civil War, would not be conceived for another four to five years. Guy Fawkes was a 24-year-old mercenary busy on the Continent fighting for Spain against the Dutch. William Shakespeare was in London and in the early years of his career. His plays were being performed by the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, of which he was a member, at The Theatre in Shoreditch. It would be another five years before the famous Globe Theatre was built in 1599. Several of Shakespeare’s famous plays, including Romeo and Juliet, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and Hamlet were still of the future when Bartolomeo held and read this letter. It is a fascinating possibility that the original owner of our letter could have enjoyed early performances of Shakespeare’s plays and have watched the playwright himself act upon the stage.

The Paper

Letters at the end of the 16th century were mostly written on paper, as is this letter. Parchment, made from animal hides, was more durable but also more expensive and so was mostly reserved for official documents. Paper was handmade from linen and hemp rags. Old shirts, sheets, and tablecloths were commonly used. It is intriguing to think that the paper this letter was written on may once have had a previous life as part of a Florentine’s shirt! Some paper manufacturers included watermarks on their sheets but there is no such mark visible on the letter.

The Ink

Iron gall ink was used to write this letter. Simple to make and long-lasting, iron gall ink was widely used from the 5th century to the 19th century and is still available today. As its name suggests, the ink was made from galls, commonly found on oak trees, and iron, in the form of ferrous sulphate.

Once applied to paper the ink would darken over time as it oxidised. Iron gall ink adheres permanently to the paper or parchment to which it is applied. Unlike other inks it can not be erased. In order to remove a mark made with this ink, the surface would have to be scraped away with a knife. The downside to iron gall ink is that it is acidic and so over time it will eat away at the material to which it has been applied. The corrosive nature of the ink is evident in places within our letter.

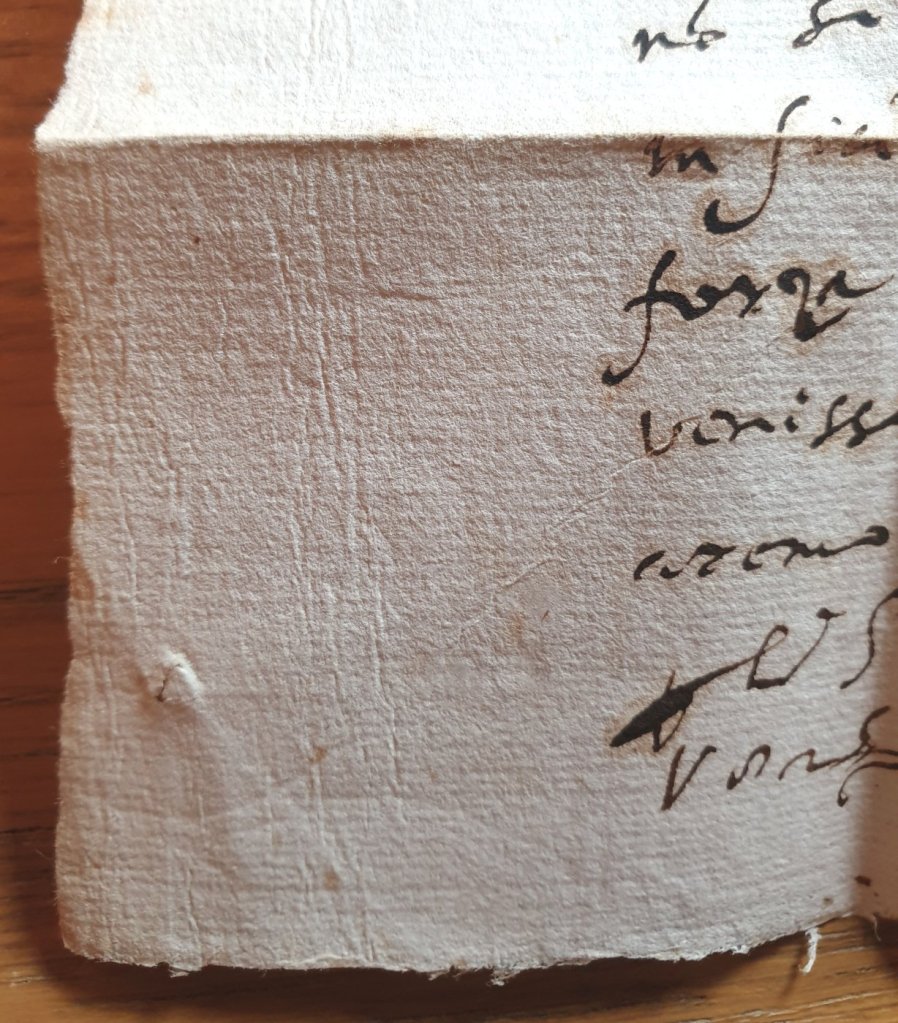

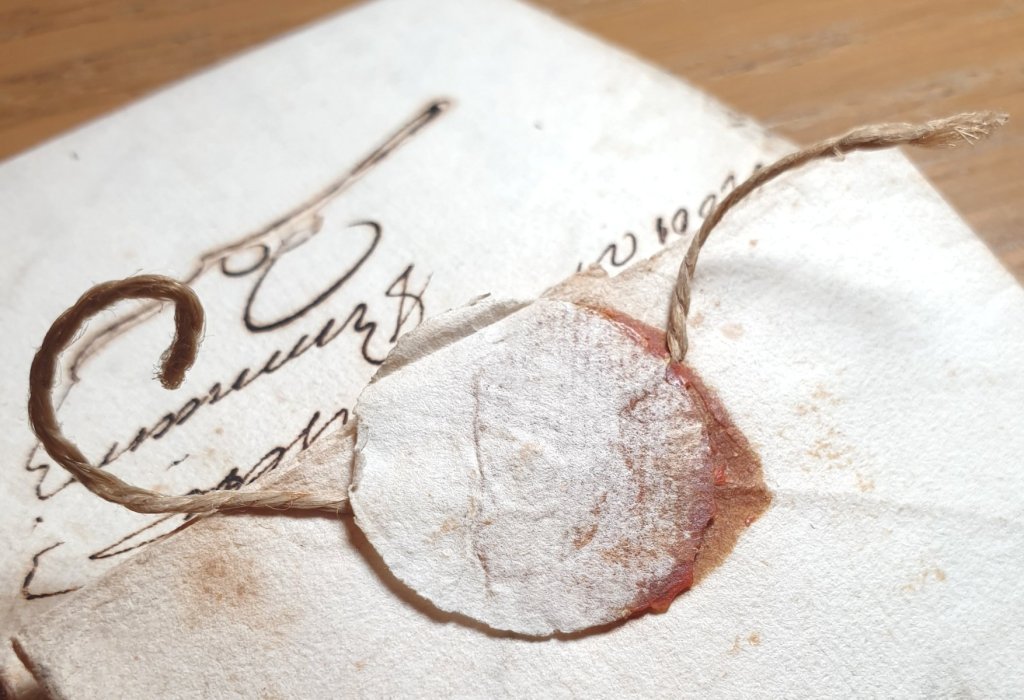

The Wax and String Seal

The letter was tied shut with string. Red wax was poured over the knot and a thin wafer, made from flour and water, was placed on top. The wax, wafer, and string are still present. String is such a mundane material but in the context of this letter it is rather wonderful. Florentine twine cut in Tudor, Elizabethan London.

What’s Next

Clearly I (and surely you, reader) would like to know what the letter says. It is written in Italian, which is not a problem, but the cursive handwriting is hard to read in many places. I shall need to find someone who can provide a transliteration. When that happens I’ll create Part Two of The Corsini Letter.

5th January 2026

Leave a comment